The Marine Biological Association (MBA) has been famously linked with three historic Antarctic expeditions, Discovery (1901 to 1904), Terra Nova (1910) and the ill-fated Endurance from 1914 to 1917.

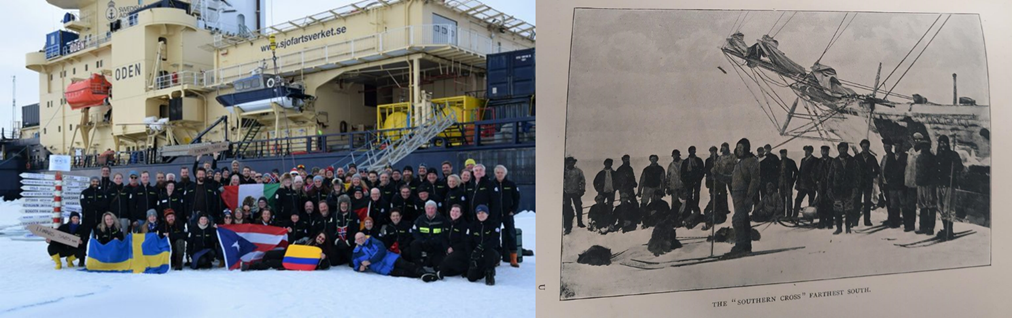

In 2021, MBA marine biologists yet again took part in an important polar expedition. Dr Kimberley Bird and Dr Birthe Zäncker joined the Synoptic Arctic Survey (SAS) on an expedition to the Arctic Ocean to find out about life beneath the sea ice.

Dr Bird explores the expeditions of the past, how they compare with her experience aboard icebreaker IB Oden and how researchers conduct scientific research in some of the harshest environments in the world.

Motivations

Similar to today, polar expeditions were strongly motivated by scientific research. However, the expeditions of the past were also spurred on by the promise of geological discoveries and to a certain extent, the “patriotic ambition to uphold the honour of his flag”.

Whilst collaborative partnerships across nations did exist historically, this was likely more to do with funding than a need to work together towards a common goal, and in fact each nation would be competing to be the first to make the discovery or plant the flag on new land.

Today polar research is often collaborative driven by a need to understand and protect this now vulnerable habitat.

Although comparatively today more people can access polar regions it is still a privilege and an experience not afforded to the masses and one that in generations to come may not be possible.

Men go out into the void spaces of the world for various reasons. Some are actuated simply by a love of adventure, some have the keen thirst for scientific knowledge, and others again are drawn away from the trodden paths by the “lure of little voices”, the mysterious fascination of the unknown.

Ernest Shackleton, Anglo-Irish Antarctic explorer

Funding

Polar expeditions are costly and require a lot of planning. Funding has to be sort from governments, societies, companies and private wealth. Failure or success can depend on the interest, scientific needs and plausibility of success, cost versus benefit of your proposed expedition. This is true for both past and present-day expeditions.

I think it was a harder task historically as expeditions would have been far riskier, often requiring the commission of a new ship that you may not get back and taking years to complete.

In 1900, Discovery cost £51,000 (£8 million today) in comparison the new RRS Sir David Attenborough cost £200 million.

Today many countries have dedicated polar research vessels that carryout multiple shorter scientific expeditions to the polar regions each year.

Preparation

Preparation for an expedition appears unchanged through time. There is great deal of effort and time spent planning and packing for an expedition; and participants must be fit and have medicals to sail. There is also as much food, supplies and scientific equipment crammed into the ship as possible.

Thanks to modern ways of storing and preserving food (and less reliance on livestock!), it is easier to bring and prepare sustenance for long voyages.

Accessibility

In the past, strong healthy men deemed capable of surviving extreme environments took part in polar expeditions.

Due to societal change and improved resources, a wider demographic is able to take part in these voyages.

These journeys still take us to inhospitable places, but the ability to survive and operate here has greatly improved with advances in technology, equipment and our understanding of polar environments much of which is owed to those early expeditions.

That said, daily life onboard shares familiarity with the past. Ships operate around the clock and everyone on board has their part to play. There is work to be done, ground to be covered, decisions to be made, food to be eaten, cards to be played and sleep to be had.

The ships

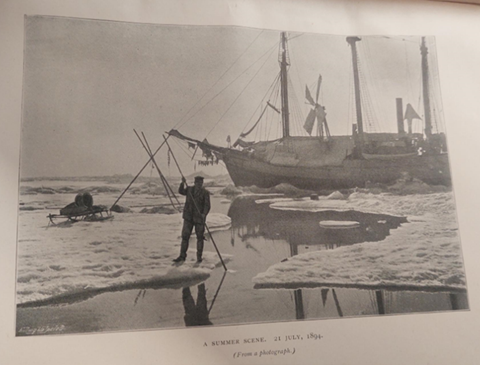

The ships ‘ice breakers’ are specifically designed for travelling through ice, with thicker and special shaped hulls for moving in ice, the difference then and now being the materials and power.

Historically ships were of wooden construction and powered by coal (steam) and sail. Modern ships are diesel powered and constructed from steel.

Travelling through Ice

Accounts of moving through the ice are familiar, describing excitement and awe of the first glimpse of ice, the sound of the boat groaning and ice cracking as you move through it and jolts when you hit a large or thick ice floe.

On the Discovery they used a balloon to get a better look ahead of what was before them, on Oden we used a helicopter to scout ahead to see what the floes were doing and find a suitable path forward. I like this comment about the noise of traveling in ice: “I remember well the difficulties of a sleep, even if tiered out by hard work”. I also found it hard to sleep on occasion from the noise of ice passing through the propellors which our cabin was above.

Today the ice in the Arctic is much thinner than the ice encountered by our predecessors – five metres with more and more ice being no more than one to two metres thick.

During Discovery’s voyage of the northwest passage, the ice was estimated to be 12 metres thick. If it were still this thick even with Oden, one of the world’s most powerful non-nuclear-powered icebreakers, it is unlikely we could have carried out the SAS expedition to the north pole.

“This great ice, which the Investigator had afterwards to battle with appalled even a race whose lives were spent in its neighbourhood.”

“Esquimaux pointed at that vast and mysterious sea of ice, which lay away to the north-west; a sea which ship could not sail through, nor man traverse.”

Polar bears

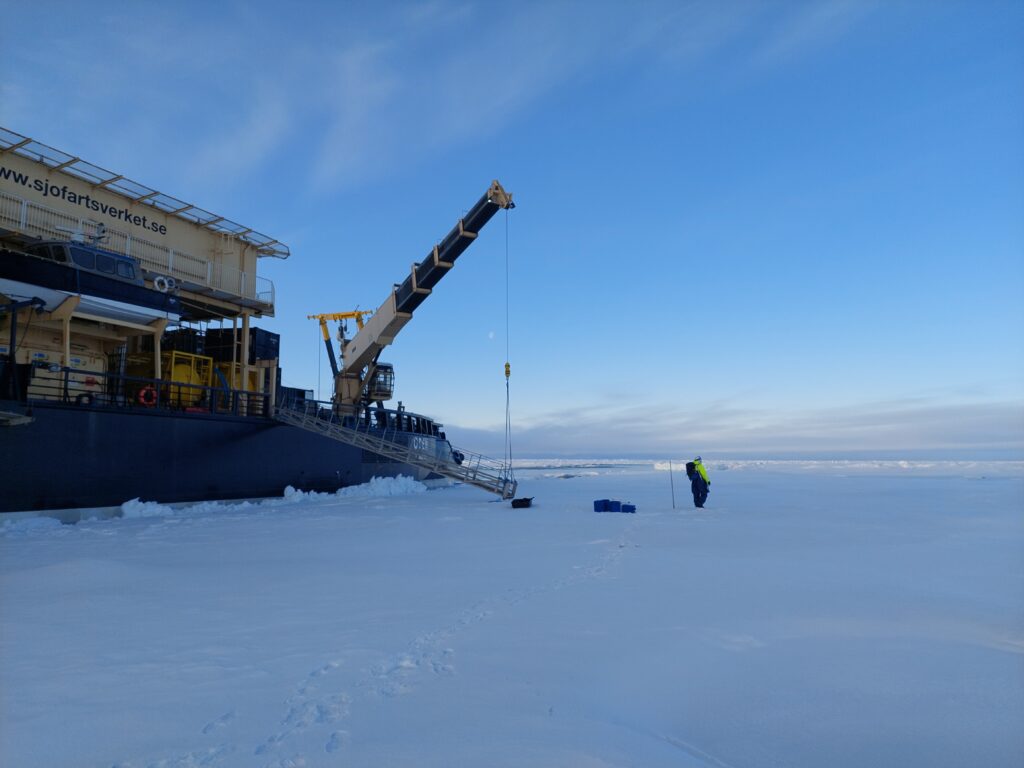

The esquimaux described the Arctic as the land of the white bear. Polar bears were one of the serious dangers when we were working on the ice, so we had to work fairly close to the ship so that we could return quickly, and we were guarded the whole time by dedicated ‘bear guards’ watching all around us for signs of a hungry bear approaching (the guns are to scare).

On one occasion the ship lost its position in the ice and drifted away from us, we were told to stop working, pack up and be ready to get back on board as the ship was going to re-position to collect us.

In that moment I remember feeling extremely vulnerable as our only mechanism to survive in this environment was much further from us than we’d like! Luckily no bears found us in our moment of isolation, and we were all returned safely to the ship. It was a humbling reminder that polar regions even with all our equipment and knowledge are just as extreme today as they were back when the first explores ventured into this mysterious land.

Isolation

Reading through the historical accounts one thing that is stark is the sense of isolation felt by those who partook in these expeditions. They were setting off for a year maybe two into the unknown and the possibility of not returning. I was excited to get the opportunity to go into the Arctic and although there were still dangers, I did not hesitate or contemplate the possibility I would not return.

However, were we destined to fail in our fight, we would not have given our lives in vain. For our sacrifice would, perchance, lead future expeditions on to success without further sacrifice.

Carsten Borchgrevink, Norwegian explorer

The Marine Biological Association shared news in almost real time, thanks to satellites friends and families could track our progress and we were able to write home sending emails out once per day.

In today’s world that is still fairly isolated, and you do feel a sense of being cut off and your life support being solely dependent upon the ship and your fellow seagoers.

Historically news would only reach home when another ship came to re-supply or on your return. I imagine many people would only hear about expeditions through news reports and the accounts (such as the reports held at The National Marine Biological Library) accessible only to the more learned society.

Perhaps with the exception of the dedicated scientists that took part, the majority of expedition participants would return to their lives and other jobs. Today other than the ship’s crew, the bulk of participants are scientists with specific questions to answer. The data and samples they collect are returned to be worked on by their respective labs and results published in scientific journals many of which are open access for anyone with interest to read.

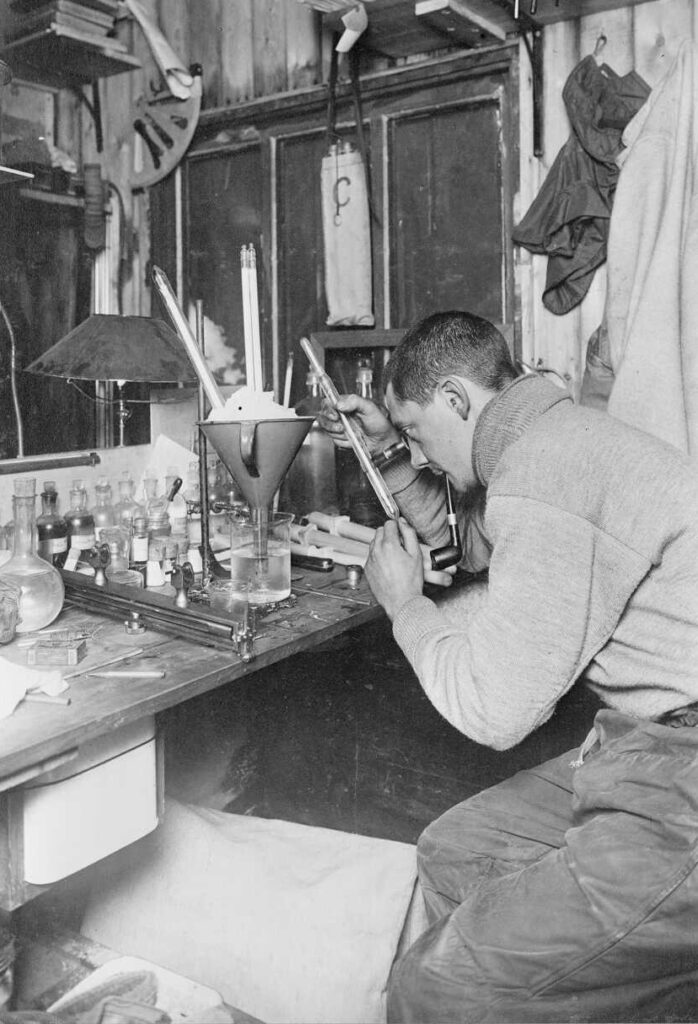

Science and laboratories

Science then and now consists of making observation taking measurements and collecting samples, but with advances in knowledge and technology the type and quantity of data we are able to gather is increased.

Measurements such as salinity and temperature are still recorded, but with advances in automation we can record these physicochemical variables almost continuously for extended periods of time.

Specialised equipment and powered winches allow for a greater variety of samples to be collected such as seawater, sediment and plankton samples from the seafloor to the ice surface.

Satellites and imaging technology allow us to get accurate positions and map our surroundings and the seafloor. Computing technology and batteries allow us to leave equipment in situ and record data in real-time.

The labs on board today are almost akin to those we use on land. Ships have purpose-built labs and can carry container labs to increase space and for specialist requirements.

Clothing

Although clothing styles and materials have changed over time, the way researchers and explorers dress have stayed the same, with layers of insulating garments and warm or waterproof coats essential for the harsh arctic environment.

Today most materials worn are synthetic, but previously natural materials such as wool, animal skins and flannel cloths were used to protect against the elements.

Russian felt boots or ski boots were worn on the feet and long woollen half mitts with fur mittens over the top. Head coverings were a hood (balaclava) and camel hair hat with added ear and nose covers.

Leisure Time

On a ship there is always work to be done, and everyone on board operates on a strict routine.

This remark rings familiar: “I do not remember a time when there was not a great amount of work to be done.”

When researching leisure time from past expeditions, it felt like activities are very similar to today. These include playing games, holding tournaments, exercising, reading and doing crafts, playing practical jokes, holding scientific talks and resting in your quarters.

Facilities are improved on modern ship, most of which have a gym, sauna, cinema and lounge space and everyone has a cabin with a bed.

In the past some officers would have had a cabin but the accounts from Discovery expedition state that the hammocks were preferred as they were drier and stowed away to make more space than a bunk.

Food

It is true that a ship runs on its stomach! Meals are a set routine and much looked forward too by all on board. Reading the accounts from past expeditions; it seems food was generally enjoyed although was very repetitive compared to the menu choices available today.

In the past, food was harder to preserve and keep for long periods of time. Fresh meat was provided by keeping livestock and hunting and other goods were preserved as tinned or dried products.

Freezers and improved preserving methods in modern times means ships can carry enough food to sustain everyone for the duration of the expeditions. However, some fresh food can become scarce near the end. I recall fresh vegetables and fruit started to run out by the end of our expedition, and I started to look forward to a nice salad on my return.

Here’s a typical menu from Discovery:

Breakfast was porridge. Dinner would be soup or seal or tinned meat and jam or fruit tart. Tea would be bread and butter and cheese or jam with the traditional ration of rum according to naval tradition (this is not a tradition that is not upheld today as most ships are dry).

On Oden between mealtimes, we could buy chocolate and crisps, sweets and ice cream. There were often some delightful freshly baked goods available at coffee breaks. On both past and present expeditions, a good baker on board was essential to provide the all-important fresh bread and cake to sustain the crew!

To find out more about the Synoptic Arctic Survey, please visit the website: https://synopticarcticsurvey.w.uib.no/

Discover more about the MBA’s integral role in Arctic expeditions and pioneering marine research.