Crinoids, (known commonly as feather stars and sea lillies) are part of the echinoderm group that includes sea urchins and sea stars. They have shown incredible morphological and biological properties that could inspire future innovations.

Dr Angela Stevenson, Senior Research Fellow at the Marine Biological Association is on a mission to discover more about the ecology and biology of these amazing marine invertebrates.

Inspired by nature

“I grew up by the St. Lawrence Estuary – it was literally my front yard – in St-Nicolas, Quebec, Canada. Next to my family house was a tributary with a little waterfall, surrounded by vast forests. I had nature and water all around me, it was difficult to not be curious about it.

The area where we lived was remote, somewhat of a retirement location, so this meant there were few kids or people around most of the year. So, I spent my evenings and weekends playing in the river at high tide and the estuary at low tide. I never felt alone…the incredible biodiversity around me kept me totally captivated. You could say I studied plants and animals in real time, every day, every season, for the first 18 years of my life.

I’ve had many wonderful mentors throughout my journey, but nature itself has been my greatest teacher and closest friend really.”

Making a difference

“Over the years, I witnessed changes in the ecosystem – amphibians near the tributary became harder to find, large fish started washing up on the shoreline (once, even an ancient sturgeon!), and fry populations declined, eventually they disappeared.

It just didn’t look like the lush and vibrant nature I had played with all my life. My young brain knew there was something different and bad about it.

It is this shift that sparked my curiosity about ecology and a desire to make a difference. This passion led me to enrol in a degree in Marine Science at UBC in Vancouver, British Columbia, where I truly discovered the marine world.

As soon as I could, I earned my diving license, which opened countless new doors. I finally connected face-to-face with the animals I had admired since childhood.”

The fascinating world of crinoids

“Regeneration is widespread among the animal kingdom, but crinoids (all echinoderms really) have an exceptional regeneration ability, and can regenerate most body parts from very little tissue. For example, a salamander will regenerate approximately 4 mm in 6 months, while a crinoid can regenerate up to 1.5 mm per day.

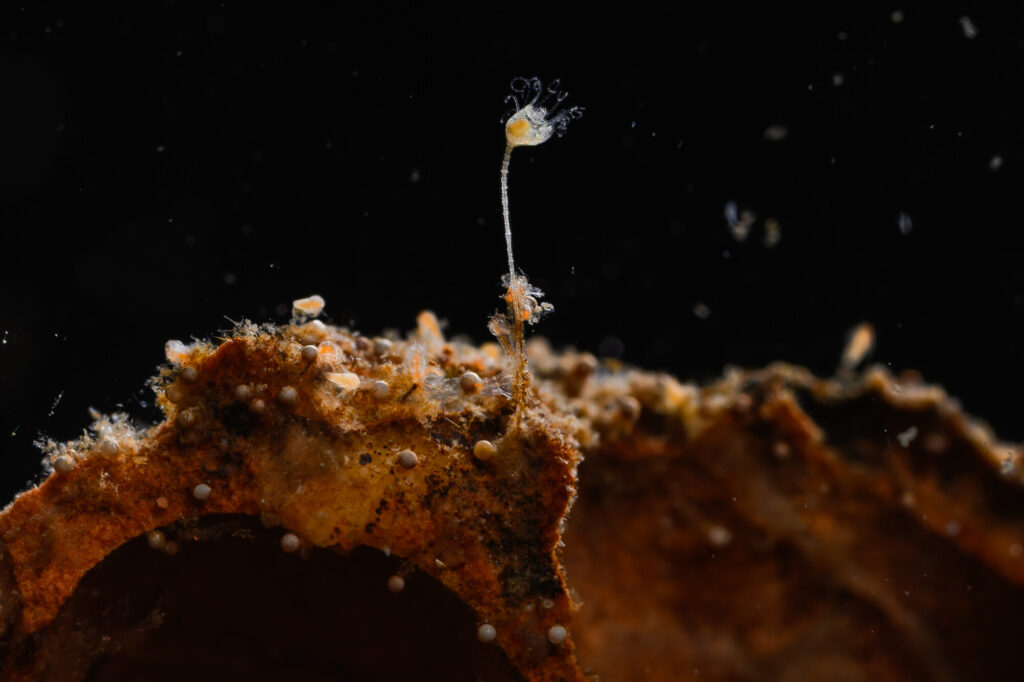

This crinoid (below) has obviously seen better days, it looks like it was stressed or attacked by a predator and lost all of its arms. It even autotomised its stomach, but still it is alive and even regenerating all of its arms.

We have half a billion years of records about these animals, they have ephemeral injuries, and host a quite vibrant metropolis of organisms. I’ve counted up to 10 different taxa, and 20 visible individual on a single feather star!”

What can we learn from crinoids

Crinoids are quirky animals with interesting biology and ecology. For example, their ligaments, functioning like energy-efficient muscles, and their ancient skeletal structures, preserving 500 million years of evolutionary knowledge, could offer unparalleled perspectives on past ecological interactions, motility and environmental adaptation. This work bridges evolutionary biology, biophysics, and bio-inspired engineering, shedding light on the past while inspiring future innovations.

They also have interesting biological properties. Mammals have limited potential to regenerate organs, and other vertebrates, like amphibians have some regeneration abilities, but none compared to that of crinoids, which can rapidly regenerate limbs and most organs. Understanding this ability in crinoids, if successful, could pave the way for future cell-based therapies.

Find out more about Dr Stevenson’s work by visiting her research page, Benthic Ecology and Crinoid Biology at the MBA.