By Cynthia Mansell and Chris Bennett, National Marine Biological Library (NMBL) Volunteers

During the 2nd World War there were several air raids which affected the Marine Biological Association (MBA) and the people that worked and lived there.

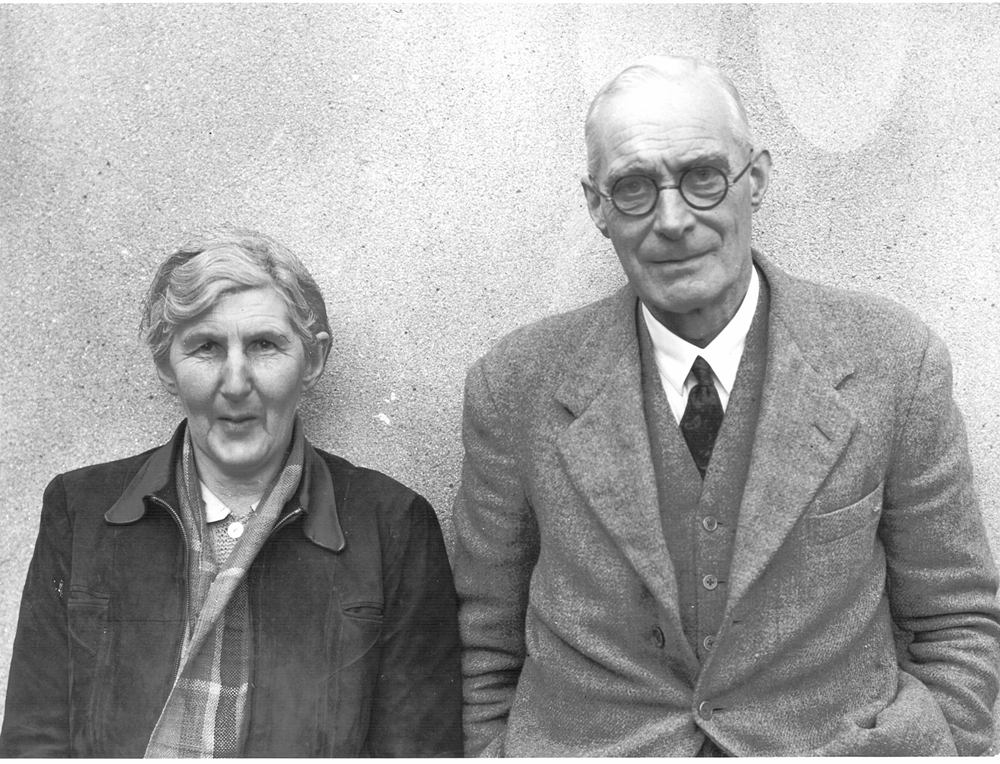

Dr Stanley Kemp at the time was the Director of the MBA and he, his wife and daughter Belinda had living quarters in the eastern part of the building and including what is now the common room.

Dr Kemp adopted the view that “there would be no bombing from the air, and if there were aerial bombing Plymouth would escape it”. The reasons being that the oil storage tanks had been emptied, the docks were insignificant and Plymouth was not on one of the main air lanes.

At the same time Miriam Rothschild was working at the MBA solving trematode lifecycles. She had also qualified as an Air Raid Warden and she had a patriotic side line of producing chicken feed made from seaweed.

Belinda Kemp (Baldock) was aged 17 at the time of the first air raids on Plymouth. She remembers that they “lived over the shop” – “bedroom being a corner of the common room”.

According to a letter from Dr. Kemp dated September 1949 “the ARP (Air Raid Precautions) shelter in the tunnel was almost ready – bags were unobtainable so we got hessian and made them ourselves; 500 in three days”. The tunnel led to the pump/boat house on the foreshore. The Laboratory was only supplied with stirrup pumps and gas masks when the raids began.

During a raid in 1940, Dr and Mrs. Kemp, Miriam Rothschild, Belinda and others spent the night in the tunnel to the boat house while the bombs fell around them. When Belinda asked if she was frightened, she replied “No I have no imagination; I can’t believe I won’t be alive tomorrow”. That raid finished at 4am the next day to discover the oil tanks burning and a thick pall of smoke over everything. Eventually Dr Kemp suggested that they all go to his house and try to boil a kettle and get some sleep in deck chairs. Following the cups of tea Mrs Kemp divided the sexes and ushered them into separate rooms.

The following day Miriam Rothschild discovered the door to her room had gone and there was a huge pile of splintered glass together with note books, manuscripts, snails, microscopes, tubes, shelving, jars – all of which were gone, pulverized. “Seven years of work vanished”. The sole survivor in her room, “picking its way delicately among the debris was my tame sandpiper, a red shank” Afterwards Miriam worked a 16 hour day, rearing snails, counting Cercariae, measuring shells etc.

A bomb that fell near the laboratory in 1940 broke 163 panes of glass, but the library was untouched and the new laboratories on the second floor of the main building were also not damaged.

Also in 1940, the MBA Aquarium was partly demolished in an air raid and according to Miriam Rothschild’s account; one student was found standing knee deep in water with conger eels thrashing around him.

An air raid in March 1941 high explosive and incendiary bombs fell in the vicinity of the laboratory – one behind the Directors house, much structural damage was caused and the Directors house was completely burnt out. The library was intact except for loss of windows and skylight, which was quickly made weatherproof. Amongst others the Director’s garage and store and the constant temperature rooms all sustained considerable damage.

In a letter of April 1941, Dr Kemp notes that there had been heavy raids which did not cause harm but a bomb disposal squad safely removed 3 delayed action bombs, one of which being next to his demolished garage. He stated that he was about to rent a house near Tavistock in the name of the MBA as his residence and for housing the Library. This would be Hawkmoor House.

As for Miriam Rothschild. Following her work at Plymouth she left never to return and was called up to “go to decode at Bletchley”.

In a letter in the MBA archives dated 11th June 2001, Dame Miriam Rothschild FRS said she had “worked in several laboratories, including the Zoological and Anatomy Departments of Oxford and Harvard, the Biology department in Naples, and none of these large organisations gave one the inspiration of the smaller and more personal influence of the one in Plymouth”.

These personal recollections were uncovered in the MBA’s archive, which holds a wealth of material relating to the running of the MBA and the work and lives of those based at Citadel Hill. Records of much of the material are available on The National Archives Discovery pages – to find out more please contact the Library nmbl@mba.ac.uk