This week as many celebrate International Day of Women and Girls in Science, we’ve put the spotlight on one of our female scientists.

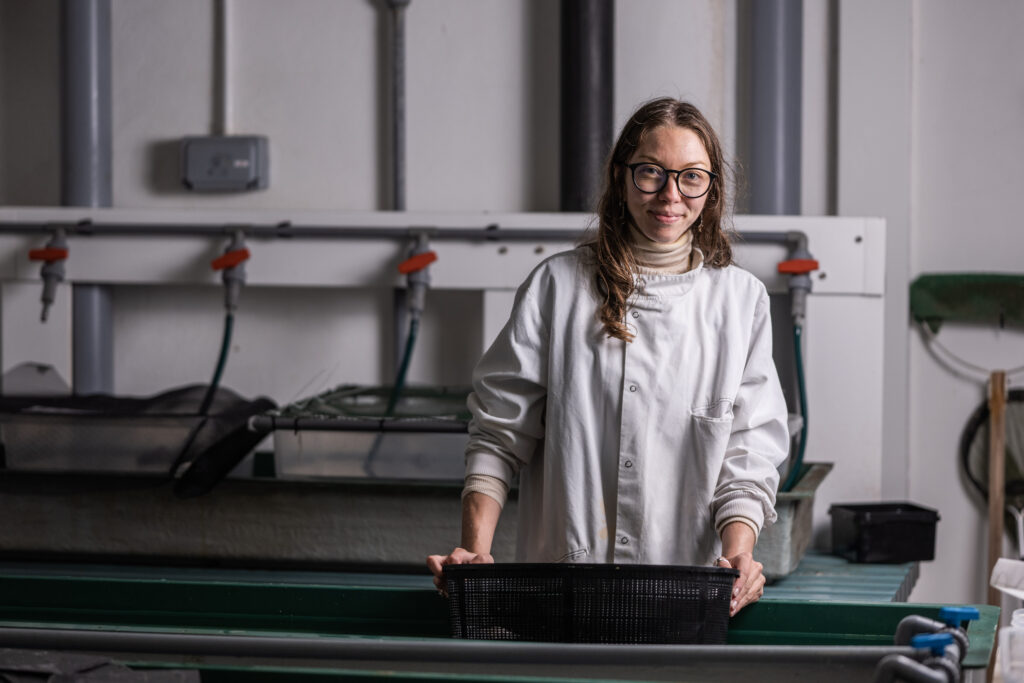

Kesella Scott-Somme, Research Assistant on the Darwin Tree of Life project team at the Marine Biological Association (MBA) talks about her experience as a women in marine biology and how inclusivity is key in all STEM subjects.

“In 1878, UCL was the first British university to open its degrees to women. I went to UCL to do my masters in 2015. I tried to imagine what it might have been like to be one of those first women to study there. Finally able to work and have my achievements recognized, walking alone up to the imposing iron gates with fear sitting heavy in my gut. It may have been a progressive move for the university at the time, but I can’t imagine that the response from the men that worked and studied there was universally warm.

When I actually walked in on my first day, no one looked my way twice, the crowd streaming in and out the gates was diverse, I saw lots of people who looked like me, and lots of people who didn’t. I felt nervous, but I wasn’t afraid. Science is getting better, and diversity within STEM is growing, but there are still so, so many barriers to entry, and to success for so many people. Supposed ‘minority groups’ of gender, sexuality, skin colour, religion, ability and anyone else who doesn’t fit a ‘standard’ (and actually make up the majority of our world) are often turned away from STEM careers by barriers that should not still be standing.

After many years of trying different things, I found my own niche in the science community, but I have many issues with the exclusivity of a science career. Science has been a mysterious elitist world for too long, it’s a huge field and there is space for everyone. I didn’t do amazingly well at school and I was kicked out of college at 16, I was definitely never encouraged to follow a STEM career (in fact I remember several occasions when I was actively discouraged).

I often feel like I’m not smart enough to be a scientist, I have three degrees and many years working in this area, but imposter syndrome is common in a profession that is set apart by society as being for smart people only. I have dyscalculia, a mathematical learning difficulty that has often left me feeling stupid. When I was diagnosed with it in my first year of university, I felt relieved to finally have an excuse for when I make mistakes. But I also felt disappointed that my brain was probably never going to pick up some of the more difficult mathematical concepts. And it has been a struggle, there have been times I’ve felt like I was working so much harder than everyone around me and yet somehow achieving so much less, times where I’ve been in a room full of people who got ‘it’ when I didn’t.

At these times I remind myself that having a mind that works differently to those around me is an advantage, I can bring something to the community that might be missing, and every single other person around me is doing the same thing, bringing something different to the table that allows us to look at the world in a different way.

There are lots of different kinds of intelligence, and we don’t have reliable ways to measure any of them. Just because you didn’t do well on exams doesn’t mean you wouldn’t be of value to your desired STEM community. Having a STEM career is a lot more than just ‘book smarts’, some jobs require a steady hand, a keen eye, or the right mind to be able to do several things at once in a complex order. If you are interested in a career in STEM, all you need is an interest, focus and persistence. There will always be those that try to protect the exclusivity of science by saying it is important to only have ‘highly intelligent’ people working within it, but if intelligence was all you needed we would have a lot more diversity at the top.

Every person has their own battles, and it is so important that individuals feel respected, valued and welcomed in the STEM community. Whenever we fight for more inclusivity, we need to be thinking of all the groups that are affected and we need to make sure there are safe and healthy work environments that can allow anyone to thrive. Ultimately, if you are worried that your gender, sexuality, skin colour, religion, disability or other health condition may hinder your progress in a STEM career, I can’t promise you that it won’t, but I do think you should have a go, your different brain is so urgently needed, and you can help us pave the way for a new and more inclusive way of working.”